Introduction

Diabetes is often described as a condition that silently damages the body over time. While most people are aware of its impact on blood sugar and blood vessels, fewer realize how it can physically reshape the heart. Recent Diabetes Research has uncovered striking evidence that both type 1 and type 2 diabetes alter the size, structure, and function of the heart muscle. This discovery may explain why people with diabetes face a higher risk of heart failure, even in the absence of blocked arteries. Could diabetes be quietly remodeling your heart from the inside out?

Table of Contents

- Diabetes and Heart Remodeling: What the Research Shows

- How Heart Structure Differs in Diabetes Patients

- Clinical Implications for Treatment and Prevention

- Looking Ahead: Future Directions in Diabetes Research

- Conclusion

- FAQs

Diabetes and Heart Remodeling: What the Research Shows

For decades, clinicians have observed that patients with diabetes experience more cases of heart failure than those without the condition. However, the precise reason remained unclear. Recent Diabetes Research using advanced cardiac imaging has shown that diabetes does more than increase blood pressure or cholesterol—it fundamentally changes the heart’s shape.

Studies reveal that individuals with type 2 diabetes often develop left ventricular hypertrophy, a condition where the heart’s main pumping chamber thickens. Unlike the heart changes seen in athletes, this thickening is maladaptive, leading to stiffness and reduced pumping efficiency. Researchers have also observed that people with type 1 diabetes exhibit early signs of cardiac remodeling, even in youth. This suggests that structural heart changes may begin long before traditional cardiovascular disease symptoms appear.

One landmark study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology found that diabetes independently predicts heart muscle thickening and fibrosis, regardless of other risk factors. The implication is clear: diabetes alone can act as a direct driver of harmful cardiac remodeling.

How Heart Structure Differs in Diabetes Patients

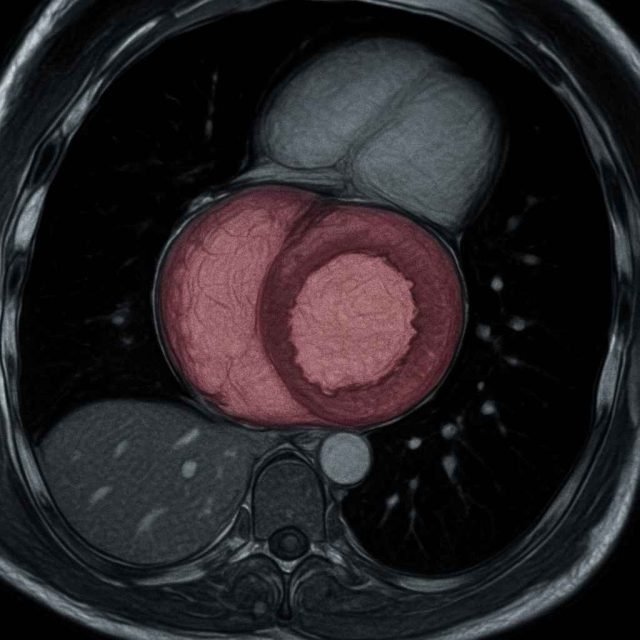

The structural differences in the hearts of people with diabetes are significant enough to change how their organs function under stress. Cardiac MRI scans reveal patterns of concentric remodeling, where the heart walls grow thicker but the chamber size remains small. This means the heart struggles to fill properly, a precursor to diastolic dysfunction.

In addition, diabetes can lead to myocardial fibrosis, or scarring of the heart tissue. Fibrosis reduces the heart’s elasticity, making it less responsive to physical activity and increasing the risk of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). This condition is notoriously difficult to treat and is particularly common among patients with diabetes.

The metabolic environment created by high blood sugar, insulin resistance, and inflammation drives many of these structural changes. Elevated glucose can stiffen heart muscle proteins through glycation, while chronic inflammation promotes scarring. Over time, even small alterations compound, reshaping the heart in ways that escape detection until symptoms emerge.

For clinicians, these findings highlight the need for earlier cardiovascular monitoring in diabetes patients. For example, incorporating echocardiography or MRI in routine checkups for those with long-standing diabetes could help detect structural changes before heart failure develops.

Clinical Implications for Treatment and Prevention

These revelations in Diabetes Research are shifting how cardiologists and endocrinologists think about treatment. If diabetes itself reshapes the heart, therapies must go beyond glucose control to protect cardiac structure and function.

SGLT2 inhibitors such as empagliflozin (Jardiance) and dapagliflozin (Farxiga) have already shown cardiovascular benefits independent of blood sugar lowering. Large trials demonstrated that these drugs reduce the risk of hospitalization for heart failure, suggesting they may directly counteract diabetes-induced remodeling. Similarly, GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide (Ozempic) are being studied for their protective effects on heart tissue.

Lifestyle interventions remain foundational. Regular exercise not only improves insulin sensitivity but also strengthens cardiac muscle, potentially offsetting structural changes. Nutritional strategies that reduce inflammation, such as Mediterranean or DASH diets, may also slow fibrosis progression.

Importantly, healthcare providers should encourage patients with diabetes to undergo regular cardiovascular screenings, even if cholesterol and blood pressure levels appear normal. Subclinical heart changes often develop long before symptoms arise. Linking patients to trusted medical resources like Healthcare.pro can provide accessible guidance for monitoring and prevention strategies.

Looking Ahead: Future Directions in Diabetes Research

The growing body of evidence on diabetes and heart remodeling opens several new avenues for study. Researchers are exploring genetic and molecular pathways that may predispose some individuals to faster cardiac changes. Understanding these pathways could lead to targeted therapies designed to halt or even reverse remodeling.

There is also interest in developing imaging biomarkers that can detect microscopic structural changes earlier than current scans. This could transform how clinicians assess cardiac risk in diabetes patients, moving from reactive to proactive care.

Furthermore, ongoing clinical trials are investigating whether combining SGLT2 inhibitors with other therapies, such as anti-fibrotic agents, can deliver even stronger protection against heart failure. As findings emerge, they may redefine the standard of care for people living with diabetes.

For professionals following Diabetes in Control articles, keeping up with these discoveries is vital. They provide both practical insights for current patient care and glimpses into how future treatment strategies may evolve.

Conclusion

New research confirms what clinicians have long suspected: diabetes doesn’t just strain the heart, it reshapes it. Structural changes such as thickening, stiffness, and fibrosis explain why people with diabetes face elevated heart failure risks. The good news is that advances in treatment—from SGLT2 inhibitors to lifestyle strategies—offer ways to counteract these effects. For patients and providers alike, the key message is clear: protecting heart health must be central to managing diabetes.

FAQs

Does diabetes really change the shape of the heart?

Yes. Imaging studies show that diabetes causes thickening and stiffening of the heart muscle, leading to reduced efficiency.

What type of heart failure is common in diabetes patients?

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is particularly common, driven by stiffness and fibrosis of the heart tissue.

Can medications reverse heart remodeling in diabetes?

While no drug fully reverses remodeling, SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists significantly reduce the risk of progression.

How can patients with diabetes protect their hearts?

Regular exercise, healthy eating, early screening, and adherence to prescribed therapies are critical preventive measures.

Should all diabetes patients get heart scans?

Not all, but those with long-standing diabetes or additional risk factors may benefit from periodic echocardiograms or MRIs.

Disclaimer

This content is not medical advice. For any health issues, always consult a healthcare professional. In an emergency, call 911 or your local emergency services.